Dennis A. Francesconi’s Art comes from his heart — and from his mouth.

By Lori A. Wood / contributing writer to Orbit Magazine / United Spinal Association.

April 2005

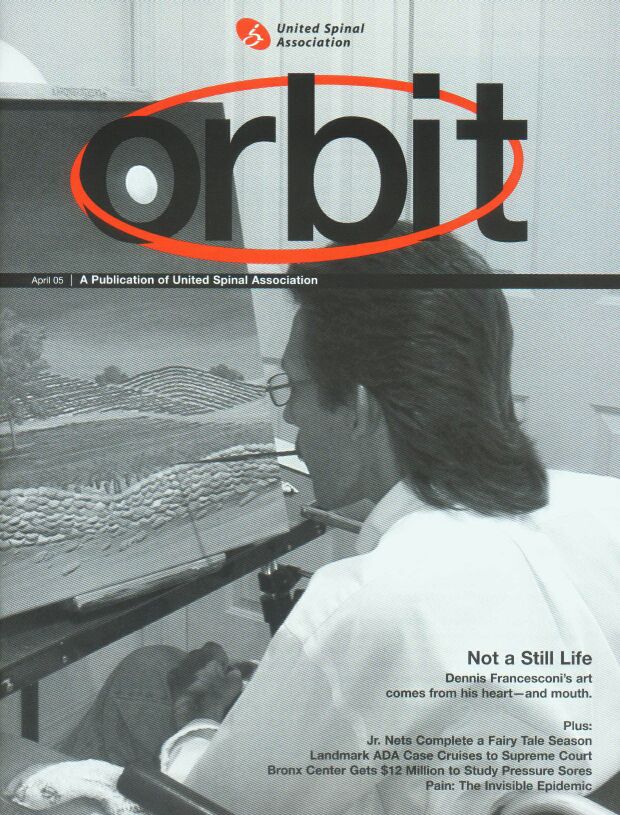

Not a Still Life

The ability to appreciate art is largely a subjective matter—a piece can be considered beautiful for any number of reasons. The work of paralyzed Artist Dennis A. Francesconi is as beautiful for the way it is created as it is for the stunning results of his efforts.

Born in Fresno, California, Francesconi had a normal, hyperactive childhood, playing sports, being outdoors, and working on his family’s ranch. “I could never sit still,” he says.

In August 1980, at the age of 17, Francesconi was on a family outing water-skiing at Chowchilla Reservoir, north of Madera, California, when, in a split second, in order to avoid crashing into rocks that came between him and the boat leading him around the reservoir, he let go and hit the shore at high velocity. “When my skis made contact, I was catapulted 31 feet right past my dad, who was sitting on the shore, and I landed flat on my head. It snapped my neck. I was awake during the whole thing.

I remember hitting the ground with my head. I went to get up, and nothing moved.” Just three weeks before the start of his senior year in high school, Francesconi had sustained a level C-5 spinal cord injury (SCI), which rendered him a quadriplegic.

Learning to Be Still

Doctors at Saint Agnes Hospital in Fresno told him that, more than likely, he’d be paralyzed for the rest of his life. “At the time, I couldn’t move anything, except my eyes,” says Francesconi. “I wondered what I was going to do in a world where your hands, legs and everything else are so important. This is a hands-on world, and when your hands are gone, that’s the loss of a magnificent gift.”

Francesconi spent 18 days in the hospital’s critical care unit, then underwent rehabilitation for two and a half months at Fresno Community Hospital. “After the first month, my arms slowly started moving,” he says. He lifted small weights, and learned to feed himself. When he returned home, he chose not to go back to high school. “When I went out in public, I felt like I was being gawked at, so I didn’t want to go back to high school, where image is so important. I thought I would stand out. I had lots of time on my hands to think. Being so immobile was hard and I was depressed. Friends would take me to do the things we used to do, but I became nothing more than a spectator.”

Francesconi coped with these developments by drinking. “I did that for about the first two years, and realized it wasn’t doing me any good.”

A Stroke of Fate

“When I had the use of my hands, I used to admire people who could draw and paint; I didn’t have the patience for it,” Francesconi says. Some nine years after sustaining his injury, Dennis learned to write, sketch, and paint with his mouth. He was tired of not being able to sign his name.

“I just grabbed that pen with my mouth and wrote my name, because it seemed like a natural thing to do,” he says. “Once that happened, I was doodling up a storm.” People took notice of these drawings, and were impressed. “I was embarrassed by it,” he admits. “I didn’t think they were very good.”

Once the quality of his sketches improved, Francesconi became involved with the Association of Mouth and Foot Painting Artists (AMFPA). “In college, as a student member on scholarship, I did seventeen paintings a year for them.” Still, artists can’t become full members just because they paint with their mouths or feet. “The quality has to be there,” he insists. In 1998, he also earned an Associate Degree in Arts from Kings River Community College.

Some artists with disabilities use mouth sticks, which extend the length of their writing or painting utensils. Francesconi prefers not to use them. “I’m a very detailed painter. The further away you get from the painting, the less detail you’re going to have,” he explains. “I bend down and grab the utensil with my mouth. Since I was right-handed before my accident, I have to get it on the right side and get a good grip with my molars. If you hold it with your front teeth, it wobbles. Most of my art is representational, meaning that you can look at it and know what it is.” He also does a few pieces of abstract art for people who attend the organization’s exhibits. “It lets me think outside the box,” says Francesconi. “I love diversity in my painting. I try not to study the old master painters, because I don’t want to become some carbon copy of them. I keep my style my own.”

Francesconi became a full member of the AMFPA in 1999, and since then has received excellent benefits, such as a contract and having his full salary paid to him, even if the day should come when he can no longer paint. He also retains full ownership of his works, ninety percent of which are watercolors.

“I don’t sell my originals. They’re like my kids,” he says. The organization has sent Francesconi to exhibits around the world. “My goal, and that of the AMFPA, is to locate and assist artists who paint with their mouth or feet. Personally, I’ve gone from nineteen years of being on public support––to complete financial independence through the AMFPA’s direct marketing and promotion of our holiday cards and calendars. I’m compelled to help others in similar situations who are interested in achieving success through art.” For further information, interested artists can visit www.mfpausa.com, or call the toll free number, 1-877-MFPA-USA.

One of his favorite paintings, Lunada, can be seen in a different way. “It now graces several thousand wine bottles, with more coming soon. The back labels carry my name and that of AMFPA. All labels were designed by me; it’s the first time an AMFPA artist has done this. It was a great feeling to see those bottles rolling off the labeling line,” he says proudly. The Lunada painting and many others can be seen at his personal Web site, www.sconi.com.

In his spare time, Francesconi demonstrates his unique artistry to schoolchildren. “After I talk to them for a few minutes, they get to try mouth painting themselves. Some of their efforts amaze me.”

Through it all, his wife Kristi has been by his side, caring for him since they were teenagers. “She has always seen beyond the wheelchair, and I have a great deal of respect for that. I consider myself very fortunate to have her in my life,” he says.

Francesconi describes his life as busy, fulfilling, and blessed. He loves what he does, and this is one of the greatest blessings of all.

Dennis was also featured on the cover of the April issue of Orbit Magazine. Many thanks to Lori A. Wood, Chris Pierson, and the United Spinal Association.